What Is a Vector?

You can think of a vector in simple terms as a list of numbers where the position of each item in this structure matters. In machine learning, this will often be the case. For example, if you are analysing the height and weight of a class of students, in this domain, a two-dimensional vector will represent each student:

Here v1 represents the height of a student, and v2 represents the weight of the same individual. Conventionally, if you were to define another vector for a different student, the position of the magnitudes should be the same. So the first element is height, followed by weight. This way of looking at vectors is often called the “computer science definition”. I am not sure if that is accurate, but it is certainly a way to utilise a vector. Another way to interpret these elements that is more relevant to linear algebra is to think of a vector as an arrow with a direction dictated by its coordinates. It will have its starting point at the origin: the point (0, 0) in a coordinate system, such as the x,y plane. Then the numbers in the parentheses will be the vector coordinates, indicating where the arrow lands:

Figure 3.1 represents a visual interpretation of the vector

As you can see, we moved from the base, point (0, 0), by two units to the right on the x axis and then by three units to the top on the y axis. Every pair of numbers gives you one and only one vector. We use the word pair here as we are only working with two dimensions, and the reason for using this number of coordinates is to create visual representations. However, vectors can have as many coordinates as needed. For example, if we wish to have a vector

In my opinion, the best way to understand linear algebra is by visualising concepts that, although simple but powerful, are often not well-understood. It is also essential to embrace abstraction, and let ourselves dive into definitions by bearing this concept in mind, as mathematics is a science of such notions. The more you try to understand abstract concepts, the better you will get at using them. It is like everything else in life. So bear with me as I introduce the first abstract definition of the book: a vector is an object that has both a direction and a magnitude:

Alright, let’s try and break this concept down, starting with direction. We know that a vector has a starting point, which we call the base or origin. This orientation is dependent on a set of coordinates that in itself is essential for defining this element. For example, look at the figure above. The landing point defines the direction of the vector

Vectors alone are instrumental mathematical elements. However, because we define them with magnitude and directions, they can represent many things, such as gravity, velocity, acceleration, and paths. So let’s hold hands and carefully make an assumption. We know nothing more about linear algebra yet, but there is a need to move on, well at least for me there is, before you call me a thief, as so far I have charged you money just for a drawing of an arrow. If we only know how to define vectors, one way to carry on moving forward will maybe be to try to combine them. We are dealing with mathematics, so let’s try to add them up. But, will this make sense? Let’s check.

3.1 Is That a Newborn? Vector Addition

Given two vectors

- You can go to a party and try to impress someone with the phrase ”translation from the edge of where one vector finishes of the magnitude and direction of the other one”; however, I will warn you that if somebody really is impressed by that… well take your own conclusions.

- This is another step into the world of abstraction, and a visual explanation will follow.

Let’s see what is happening here. First, let’s consider two vectors:

If we make use of the Cartesian plane and plot these vectors, we will have something like this:

We want to understand geometrically what happens when we add two vectors:

Considering that directions and magnitudes define vectors, what would you say if you had to take a naive guess at the result of adding two vectors together? In theory, it should be another vector, but with what direction and magnitude? If I travel in the direction of

Analytically this is how you would do this operation:

The vector

We can explore a visualization to understand these so-called translations better and solidify this concept of vector addition:

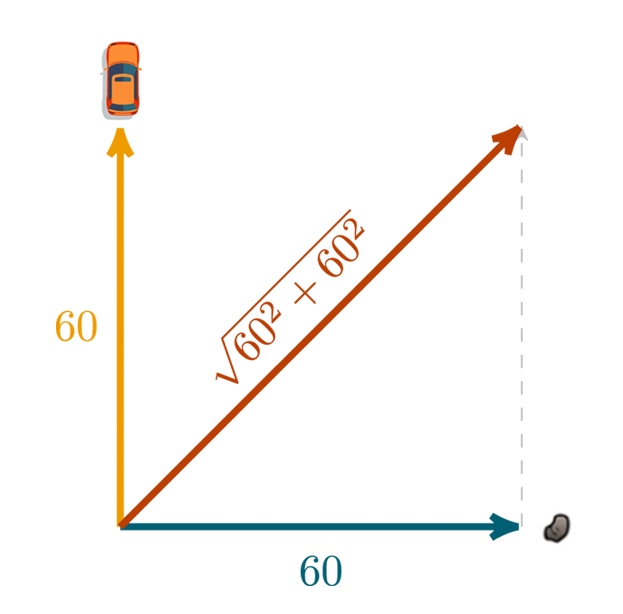

One can utilize vector addition in many real-life scenarios. For example, my cousin has a kid with these long arms who can throw a golf ball at 60 km/h:

One day we were driving a car north at 60 km/h. From the back seat, he threw this golf ball through the window directly to the east. If we want to comprehend the direction and velocity of the ball relative to the ground, we can use vector addition. From vector addition, we can understand that the ball will be moving north-east, and, if you wished to calculate the velocity, you could do so by using the Pythagoras theorem,

Well, if you can add vectors, it will also be possible to subtract them. It will be the same as if you were to find the sum of two vectors, but instead of going outward in the direction of the second vector, you will go the other way. There is another thing that one can do with a vector. We can change its magnitude and direction. To do so, we can multiply it by a scalar, a number that will stretch or shrink it.

3.2 Wait, Is That Vector on Steroids? Scalar Multiplication

A scalar can be any real number. If you don’t recall the definition of a real number, I can refresh your memory, but what happened along the way? A real number is any number you can think of. Are you thinking about a number that seems mind blowing complicated , like π? Yeah, that is a real number. Analytically we can define a real number thus:

The λ is a variable or a scalar that can accommodate any real number. The other new symbol, ∈, means to belong to something; that something here is the set of real numbers, which we symbolise as ℝ. As λ is a real number, there are four different outcomes when multiplying a vector by a scalar. First, we can maintain or reverse the vector’s direction depending on this scalar’s sign. Another thing that will be altered is the length of the vector. If λ is between 0 and 1, the vectors will shrink, whereas if the value of λ is greater than 1 or -1, the vector will stretch:

- If λ > 1 the vector will keep the same direction but stretch.

- If 1 > λ > 0 the vector will keep the same direction but shrink.

A couple more cases:

- If λ < −1 the vector will change direction and stretch.

- If 0 > λ > −1 the vector will change direction and shrink.

Symbolically, multiplying a vector

If we define a new vector

It follows:

Finally:

Because we defined λ to be -2, the result of multiplying the vector

We are now at a stage where we know how to operate vectors with additions and subtractions, plus we are also capable of scaling them via multiplication with a real number. What we still haven’t covered is vector multiplication.

3.3 Where Are You Looking, Vector? The Dot Product

One way that we can multiply vectors is called the dot product, which we will cover now. The other is called the cross product, which won’t be covered in this book. The main difference between the dot product and the cross product is the result: the dot product result is a scalar, and what comes from the cross product is another vector. So, suppose you have two vectors of the same dimension. Then, taking the dot product between them means you will pair up the element entries from both vectors by their position, multiply them together, and add up the result of these multiplications.

So, for example, consider the vectors:

We can then calculate the dot product between

A definition for this same concept given any two vectors,

|

(3.1) |

One of the goals of this series of books is for you to become comfortable with notation. I believe it will be of great value; therefore, I will describe each symbol introduced throughout the series. For example, the symbol ∑ is the capital Greek letter sigma; in mathematics, we use it to describe a summation, so:

In essence, we have an argument with an index, viwi, representing what we are going to sum. Now the numbers above and below the sigma will be the controlling factors for this same index that is represented by the letter i. The number below indicates where it starts, whereas the number above is where it needs to end. In the example above, we have two components per vector and need them all for the dot product, so we have to start at one and end at two, meaning that i = 1 and n = 2.

I learned the dot product just like that. I knew I had to perform some multiplications and additions, but I couldn’t understand what was happening. It was simple, and because I thought that computing it was enough, this led me to deceive myself into thinking that I fully understood it. I paid the price later, when I needed to implement these concepts to develop algorithms. The lack of context and visualisation were a killer for me.

A true understanding of linear algebra becomes more accessible with visualisations, and the dot product has a tremendous geometrical interpretation. It can be calculated by projecting the vector

Projections are a fundamental concept in machine learning, particularly in understanding how data can be represented in lower-dimensional spaces. They can be intuitively understood by considering angles and movement in the context of vectors.

Imagine two vectors, say

The projection of vector

into

into  .

.If we are after a number representing how much a vector points in the direction of another, it makes sense for us to use their lengths. Therefore, we need to calculate two measures: the length of

So, we know that the square of the hypotenuse is equal to the sum of the squares of the cathetus (we should, right?). Generically, we can represent the vector

When we defined vectors, we established that the landing point was essential to describe the magnitude of such elements. If we have two points, the basis of the vector and the point on which the vector lands, we can use the formula to calculate the distance between two points to derive the length of this mathematical concept. It comes that we can calculate this distance with the following equation:

Where the x’s and the y’s represent the point’s coordinates, if we now use the coordinates of the landing point and the origin to calculate the distance between these two points, we will have something like this:

Which in turn:

Because all vectors have the same origin, the point (0, 0), the length of

Where v1 and v2 are generic coordinates for a landing point.

Which gives us:

This metric can also be called the “norm” of a vector; to be rigorous, as we should be, this norm is called the Euclidean norm. The fact that there is a name for a specific norm suggests that there are more of them in mathematics, which is exactly right. There are several definitions for norms, and each of these is calculated with a different formula. We will use the Euclidean norm for most of this book.

What if we are in a higher dimensional space, will this norm scale? The answer is yes, and we can get to the formula by using the same equation for the distance between points. So, let’s try and calculate it for three dimensions, then see if we can extrapolate for n dimensions. The problem is that we are stuck with a formula that takes only two components. There are paradoxes in mathematics. Some are problems that are yet to be proven, and some are just curiosities. This one is spectacular; mathematicians do not like to do the same thing several times, so the ideal situation is to work for one case and then generalize for all. The goal is to save time so that, at the next juncture, when a similar problem arises, we have a formula that can solve it, which is an astonishing idea on paper. The funny bit is that sometimes it takes a lifetime to find the equation for the general case.

So for the next 200 pages, we will be… calm down, this one will be quite simple. So, (v1,v2,v3)T can represent any vector with three coordinates. Let’s use it and try to derive a generic equation for the norm formula. As it stands now, if we only consider what we have learned in this book, we can’t say that we are at Einstein’s level of intellect, YET! Gladly for this particular case we can get ourselves out of trouble easily:

So it comes that:

Generically the norm of a vector with n components can be calculated with the following equation:

I know this is a simple concept with a rudimentary formula, but formulas can be deceiving. Sometimes, we see them, assume that they are true, move on, and think that it is understood. The problem here is that while you can just choose to trust religion, don’t just trust science. Criticise it. The more you do this, the more you will learn. Blindly relying on everything that you are shown will appeal to the lazy brain as it removes the necessity to think about things. We can’t forget why we did all that: the dot product! Yet another magnitude has to be calculated, but this time it is of the projection of

into

into  .

.Okay, so after all of this, we have a geometrical approach to the derivation of the dot product for two vectors

|

(3.2) |

We know from previous calculations that

The norm of

Consequently:

The dot product tells you what amount of one vector goes in the direction of another (thus, it’s a scalar ) and hence does not have any direction. We can have three different cases:

- The dot product is positive,

⋅

> 0, which means that the two vectors point in the same direction.

- The dot product is 0,

⋅

= 0 , which means that the two vectors are perpendicular, the angle is 90 degrees.

- The dot product is negative

⋅

< 0 , which means that the vectors point in different directions.

This may still be a bit abstract—norms, vectors, and how they align with each other’s directions, so let’s explore an example. Imagine we are running a streaming service where movies are represented by 2-dimensional vectors. Although this is a simplified representation, it helps us understand the applications of the dot product. In our model, each entry of our vectors represents two genres: drama and comedy. The higher the value of an entry, the more characteristics of that genre the movie has.

Our task is to recommend a movie to a user, let’s call her Susan. We know that Susan has watched movie

In our library, we have two more movies that we could recommend to Susan, movies

Let’s visualize these movie vectors :

Given that we have information on Susan’s movie preferences, specifically her liking for the movie represented by vector

Recall that the dot product is expressed by 3.2, where 𝜃 is the angle between vectors

|

(3.3) |

We have a phew things to compute. Let’s start with the norms:

There we go! We are just missing two dot products:

Now for the cosines:

After calculating the cosines, we observe that its value between

The choice between using the dot product and cosine similarity depends on the specific goals of your analysis. Use the dot product when the magnitude of vectors is crucial, as it provides a measure that combines both direction and magnitude. In contrast, opt for cosine similarity when you’re interested in comparing the direction or orientation of vectors regardless of their size. This makes cosine similarity ideal for applications like text analysis or similarity measurements in machine learning, where the relative orientation of vectors is more important than their length.

So, we now have a few ways to manipulate vectors. With this comes power and consequently, responsibility, because we need to keep these bad boys within certain limits.

3.4 A Simpler Version of the Universe – The Vector Space

In linear algebra, a vector space is a fundamental concept that provides a formal framework for the study and manipulation of vectors. Vectors are entities that can be added together and multiplied by scalars (numbers from a given field such as ℝ), and vector spaces are the settings where these operations take place in a structured and consistent manner.

A vector space can be thought of as a structured set, where this set is not just a random collection of objects but a carefully defined group of entities, known as vectors, which adhere to specific rules. In mathematical terms, a vector space is a set equipped with two operations, forming a triple (O, +,∗).

If the word set is new to you, you can think of it as a collection of unique items, much like a pallet of colors. Each color in the pallet is different, and you can have as many colors as you like. In the world of math, a set is similar: it’s a group of distinct elements, like numbers or objects, where each element is unique and there’s no particular order to them. Just like how our color pallet might have a variety of colors, a set can contain a variety of elements.

In linear algebra, when we talk about a vector space, we’re not just referring to a simple set like our pallet. Instead, we describe it using a special trio: (O, +,∗). Think of this trio as a more advanced version of our pallet, where we not only have a collection of colors (or elements) but also ways to mix and blend them to create new tones. Meaning if we blend two colors (addition) we will still have a color. Or if we add more of the same color, we still have a color (multiplication by a scalar). So if we define O such that elements are vectors:

- O is a non-empty set whose elements are called vectors.

- + is a binary operation (vector addition) that takes two vectors from O and produces another vector in O.

- ∗ is an operation (scalar multiplication) that takes a scalar (from a field, typically ℝ or ℂ) and a vector from O and produces another vector in O.

We mentioned rules but what are those ?

- if

and

are two vectors ∈ O then

+

must be in O.

- λ ∈ ℝ and

∈ O then λ

also needs to be in O.

Let’s not refer to what follows as rules; let’s call them axioms, and they must verify certain conditions to uphold the structure of a vector space. Axioms are fundamental principles that don’t require proof within their system but are essential for defining and maintaining the integrity of that system. In the case of vector spaces, these axioms provide the necessary framework to ensure that vectors interact in consistent and predictable ways. Each axiom must hold true for a set of vectors to be considered a vector space. This means that for any collection of vectors to qualify as a vector space, they must adhere to these axioms, ensuring operations like vector addition and scalar multiplication behave as expected:

-

Commutative property of addition:

Don’t worry there are a few more:

-

Associative property of addition:

-

A zero vector exists:

-

An inverse element exists:

Take two more to add to the collection, and these ones are for free!

-

Scalars can be distributed across the members of an addition:

-

Just as an element can be distributed to an addition of two scalars:

The last two!

-

The product of two scalars and an element is equivalent to one of the scalars being multiplied by the product of the other scalar and the element:

-

Multiplying an element by 1 just returns the same element:

Do you need to know these axioms to apply machine learning? Well, not really. We all take them for granted. The reason that I have included them is to try and spark some curiosity in your mind. We all take things for granted and fail to appreciate and understand the things that surround us. Have you ever stopped to think about what happens when you press a switch to turn a light bulb on? Years of development and studying had to take place for that object to be transformed into a color that illuminates your surroundings.

I feel that this is the right moment for an example, so let’s check out one of a vector space and another of a non-vector space. For a vector space, let’s consider ℝ2. This is the space formed by all of the vectors with two dimensions, whose elements are real numbers. Firstly, we need to verify whether we will still end up with two-dimensional vectors with real entries after adding any two vectors. Then, we want to check that we obtain a new stretched or shrunk version of a vector that is still is in ℝ2 after we multiply the vector by a scalar. As there is a need to generalize, let’s define two vectors

So, λ⋅

We have a vector of size two, and its elements belong to ℝ, as the addition of real numbers produces a real number, therefore ℝ2 is a valid vector space. For the example of a non-valid vector space, consider the following, ℝ≠(0,0)2. This is the set of vectors with two dimensions excluding (0, 0)T. This time we have:

Adding these vectors results in (0, 0)T , which is not part of ℝ≠(0,0)2.

Since we have spoken so much about ℝ2, what would be really helpful is if there was a way to represent all of the vectors belonging to such a space. And, as luck would have it, there is such a concept in linear algebra called linear combination; this mechanism allows the derivation of new vectors via a combination of others.

The term linear suggests that there are no curves, just lines, planes, or hyper-planes, depending on the dimensions that we are working in. Here we are working with two dimensions, and a linear combination can be, for example:

Say that we name (1, 0)T as

The vector

Which is the same as:

as a linear combination.

as a linear combination.If we now replace the scalars two and three with two variables, which we’ll call α and β, where both of them are in ℝ, we get:

|

(3.4) |

We can display all the vectors of the vector space ℝ2 using equation 3.4. Let’s think about this affirmation for a second and see if it makes sense. If I have the entire set of real numbers assigned to the scalars α and β, it means that if I add up the scaled version of

|

(3.5) |

In the equation 3.5, the factors c1,c2,…,cn are scalars or real numbers. The v′s are a set of vectors that belong to the space and are linearly independent if, and only if, the values for the c′s that satisfy that equality are 0. Let’s verify if 3.4 satisfies this property:

The only way for the equality to be true is if both α and β are equal to zero. Therefore,

Now, say that instead of (1, 0)T and (0, 1)T we have

If we define a linear combination of these two vectors, this is what it will look like:

|

(3.6) |

For any values of α and β, all of the resultant vectors from this linear combination 3.6 will land on the same line. This happens because

|

(3.7) |

What we can observe from equation 3.6 is that we are not able to represent all of the vectors in the space using the two vectors,

Another thing we can learn from this experiment is the concept of span; the continuing black line is an example of a span. All of the vectors that result from a linear combination define the span. For instance, in the case of

from the perspective of the standard basis.

from the perspective of the standard basis.The grids represent our perspective or the basis, which is the way we observe

Cool, more of the same stuff, a vector on an x,y axes where x is perpendicular to y. Say that we derive a new basis, a set of two linearly independent vectors whose span is the vector space, for example,

from a perspective of a different basis.

from a perspective of a different basis.If we wish to calculate the new coordinates of

Where, v1∗ and v2∗ are the coordinates of

This will result in two equations:

By replacing the value of v2∗ in the first equation we get that the coordinates of

For example, say that we wish to predict the price of a house, and our dataset consists of two measurements: the number of bedrooms and the number of bathrooms. In this context, the vector

Should we change something? What about a basis? Sure thing! Say that we have the vector

This vector represents a house that is somewhat balanced in terms of rooms. It has three bedrooms and two bathrooms. Let’s check it from a new perspective, the one described by the new basis,

OK, so we know that 3 = w1∗ + w2∗ and 2 = w1∗− w2∗ meaning that:

Therefore:

So:

The vector

Needless to say, there is another mathematical way to perform these transformations. For this purpose, we will be making use of something that is probably familiar to you, matrices.